Analysis: A Case Study of How Laying a Foundation of Continuous Improvement Allows for Rapid Response to Student Learning

This past year, the pandemic disrupted our educational systems in ways that we couldn’t have predicted. The immediate closure of school buildings and rapid shift to online learning demanded that teachers pivot quickly to meet changing and emerging student needs.

At WHEELS, a public pre-K-12 district school in New York City, grade-level teaching teams turned to a strategy they had been honing over several years — continuous improvement. This practice, while relatively new in education, has its roots in the health care field and is defined as an incremental approach to change. Continuous improvement requires schools to break down their high-level goals into smaller steps and test these ideas in a specified time frame using a cycle of Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA). The effort must be ongoing, data-driven and built upon a shared belief that teacher teams can (and should) work together to improve their impact on student learning.

Within the NYC Outward Bound Schools network, of which WHEELS is a part, continuous improvement is also an engine for disrupting historical systems of racial and social inequity. Sixty-seven percent of the students we serve across all NYC Outward Bound schools are Black or Latino. By investigating our data and looking for gaps in outcomes, we’re able to consider why some students are doing better than others. Then, through small shifts in practice, alongside continuous data monitoring, we can work to narrow those gaps.

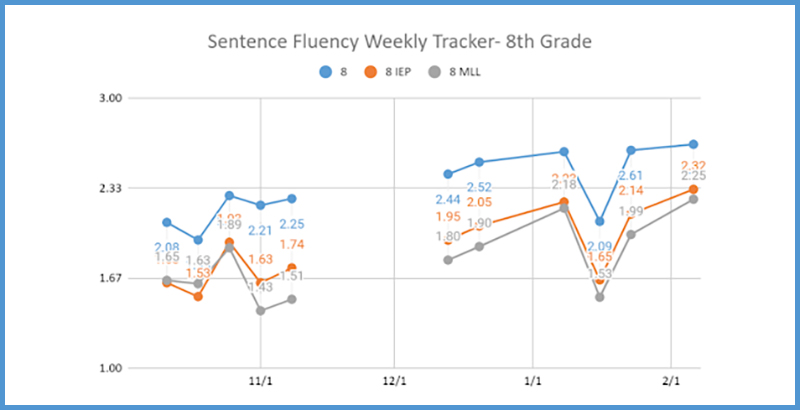

At the beginning of the 2019-20 school year, the school’s instructional leadership team set ambitious but realistic literacy and numeracy goals for all students, based on the previous year’s outcomes. Students in grades 6 to 8, for example, were to improve their quality of writing and sentence flow. To track their progress, teachers used the Plan, Do, Study, Act method by implementing small changes — having students outline their essays and better use transition words — and then studying their impact on students’ work.

While setting up and developing these inquiry cycles is one part of the continuous improvement process, it’s also necessary to adopt the problem-solving mindsets needed to foster real change. When teachers at WHEELS first started this work, they were simply going through the motions, recording data without analyzing it. “The teams were acting as technicians,” said Principal Tom Rochowicz. “They were doing all the steps of the PDSA cycle, but they weren’t slowing down, reflecting and asking their own questions.” The change came when teacher teams began to work as researchers, and were then able to make real progress toward improving student outcomes.

“After a few weeks of looking at student work in team meetings, teachers on our team began seeing student growth and the impact of collective teacher actions,” said Rachel Folger, eighth-grade team leader. “Instead of just looking at numbers, we had deep conversations about students’ writing, and we analyzed each other’s tasks and lessons to see if the strategy we were implementing was impacting student learning.”

When the pandemic hit, WHEELS was able to nimbly respond to new challenges because continuous improvement structures, practices and mindsets were already in place. The goals changed — not because literacy wasn’t still important, but because the rapid pivot to remote learning had caused a drop in student engagement. WHEELS’s new goals became increasing students’ feeling of belonging and membership in the school community and increasing engagement in their classes.

Teacher teams identified possible changes in curriculum, assessment and instruction that they believed would have a positive impact on engagement. These included designing more topical units, clearly explaining the metrics of success to students and providing a variety of supports during daily instruction time, such as note-taking templates and vocabulary lists.

In May, the team’s baseline data showed that only 67 percent of students were attending any office hours, and on average, only 45 percent were submitting assignments. By implementing these changes, WHEELS saw student engagement in office hours and submitted assignments increase over the course of the six-week inquiry cycle.

During a time with myriad challenges and little control, being able to focus on inquiry cycles and student needs was empowering for teachers.

Education leaders interested in adopting a continuous improvement mindset at their schools can begin by asking:

Where are we going?

- Identify specific goals based on where you are currently and where you want to be.

- Name the problems you want to address and seek to understand their root cause(s).

- Include issues that affect your most vulnerable students.

What will we try?

- Propose solutions (including new or revised tasks, processes or tools).

- Test small changes (such as instructional practices or methodologies) in a Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) inquiry cycle.

Who is improving, who is not, and why?

- Collect and study data (including disaggregating data) on the effectiveness of the change.

- Make decisions based on these findings about strategies to keep, change or drop.

Schools with successful continuous improvement practices have these things in common:

- They empower teachers — those closest to students — to look at data regularly and act as researchers rather than just technicians.

- They build trust among teacher teams through collaborative work over long periods of time.

- They include both administrative and teacher leaders on their teams, which increases ownership over student growth.

Source: https://www.the74million.org/article/analysis-a-case-study-of-how-laying-a-foundation-of-continuous-improvement-allows-for-rapid-response-to-student-learning/