The pandemic forced these high-schoolers to work full time. So they’re going to class at night.

“Buenas Noches,” math teacher Jose Sanchez told each student, before asking in both Spanish and English how their days went, how work went. Addressing him as “mister” and rubbing tired eyes, each student said briefly, “Está Bien.”

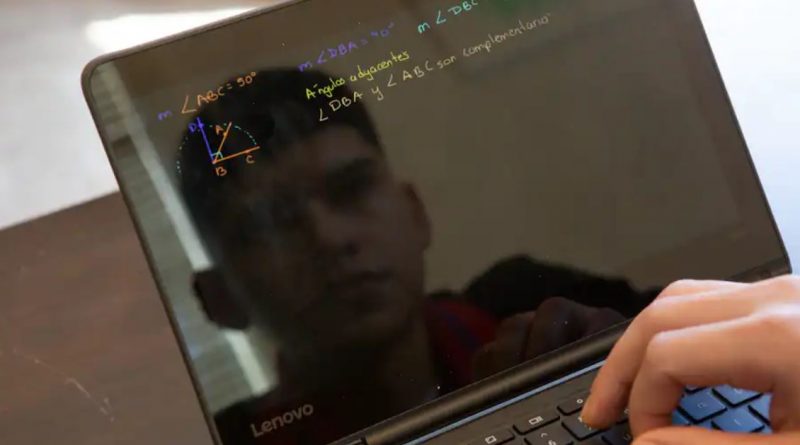

Then they buckled down to the lesson: finding the measures of angles inside triangles.

The three students are one of two dozen in a virtual night high school that Alexandria City Public Schools developed this semester. Dubbed Alternative Pathways to Achievement, or APA, the initiative is meant to accommodate students who are learning English and who must work during the day to support their families during the pandemic. It is one of the first programs of its kind in the state, although some Northern Virginia school systems — including Arlington and Fairfax schools — as well as Maryland districts have offered night schooling options for years. In D.C., a few charter schools and alternative public high schools target adult learners and struggling teenagers by offering more flexible academic schedules.

It is one of the myriad ways school officials nationwide are trying to reach children most powerfully affected by the pandemic: low-income students, those whose first language is not English and kids whose families lost jobs and financial stability because of coronavirus-driven economic shutdowns. Some school systems are offering tutoring programs, others have launched door-to-door hunts for missing children, and many are boosting their summer school offerings.

In Alexandria, a Northern Virginia city that enrolls 16,000, almost a quarter of the 3,367 Hispanic English-language learners — the term for students who are learning English — dropped out of high school in the 2019-2020 school year, according to teacher Jacqueline Rice. Alarmed by the unprecedented spike, she and fellow teacher Kellie Woodson came up with the idea for APA over the summer as part of the coursework for a degree in education policy and administration both were pursuing at Virginia Tech.

This student population was already vulnerable — many of them already balancing their schooling with a job — before the pandemic, Woodson said. But the advent of the virus narrowed their employment choices, forcing them to choose between their education and a paycheck. “Before the pandemic, they could do work in after-school hours” in industries such as restaurant service, Woodson said. “But now due to the pandemic, they’re full time during the day. It’s literally impossible for them to be students.”

That is the situation for Samuel Argueta Romero, one of the students in Sanchez’s nighttime math class who works at a restaurant from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. many days of the week. Romero is 20 and still in high school because of a Virginia Department of Education law that requires school districts to allow English learners extra time to graduate, given they must learn a new language on top of traditional coursework.

Romero has to work so he can pay rent and send money to his family, he said, many of whom are still living in his home country of El Salvador. Romero, who immigrated to the United States three years ago, lives with one of his brothers in Alexandria.

The pandemic closed the restaurant Romero used to work at, he said, where he was able to select afternoon and evening shifts. When he finally found a job at another restaurant, he learned it would require working in the daytime — in direct conflict with school.

Romero was unhappy. He had come to the United States seeking a better life, he said. Obtaining a high-school degree would allow him to win a well-paying and respectable career, he was sure, even if he didn’t yet know exactly what he wanted to do with his life.

But restaurant jobs had become scarce, and he felt he could not refuse this one, even if it meant missing school. “I felt lost,” Romero said in Spanish of the months-long period this year when he stopped showing up to class, “like I was losing the year and my schooling.”

When school counselors alerted him to APA because of his many absences and failing grades, he was eager to try it out. He is taking the night version of the four remaining courses he needs to graduate — geometry, earth science, world history, and English 12 — and is now on track to earn his high school degree this spring.

It is hard to squeeze in schoolwork around work commitments, Romero said. And it is hard to force his brain awake for Sanchez’s math lessons after a long day at the restaurant. He feels tired and stressed most of the time. But, he said, he knows it’s worth it.

APA classes take place twice a week, on Tuesday and Thursday, from 7 p.m. to 9 p.m. In addition to Romero’s course load, the program also offers courses in algebra, world history and Virginia history. And “we’re working on science,” Rice said.

So far, a half-dozen teachers are involved in the effort, either donating their services — like Sanchez — or shifting their hours so they count as part of the regular workweek. Most of the students they are instructing are between 18 and 22, Spanish-speaking, and trying to finish up their senior year of high school.

Alexandria identified student participants by working with counselors at the International Academy at T.C. Williams High School, a long-running program targeted to non-English-speaking students and recent immigrants. The counselors pointed out students close to graduation, pre-pandemic, who had stopped showing up to school and failed some of their classes.

APA allows those students to retake the classes they did not pass, Rice said. They must have failed a class to be eligible for the night-schooling program. But Rice hopes to eventually broaden the initiative to include all students whose family situations require them to work during the day.

Although it’s too early to tell for sure, Rice and Woodson said they hope many of the high school seniors enrolled in APA will graduate this spring. Their goal is to boost the graduation rate for Hispanic English-language learners by 5 percent overall by the end of the 2021-2022 school year.

Teacher Gabriel Elias, meanwhile, who is giving history lessons to APA students, is drawing encouragement from tiny moments of triumph in the quest for graduation.

One student disappeared from Elias’s lessons last semester, and the family did not respond to his frequent attempts to contact them. That student is now showing up regularly to APA classes, Elias said, and is proving himself to be “very sharp, with great English.”

It’s not a total fairy tale, Elias said. There are hiccups, including the fact that the student sometimes texts Elias complaining he does not see why he has to study the ins and outs of the American Revolution when all he wants to do in life is work as a mechanic or repair iPhones.

“I told him I like iPhone repair. Just come on Thursday [to night school] and we can talk about it some more,” Elias said. “Just making that relationship work that couldn’t happen last semester is the best part of my day.”

Sanchez said it’s the same for him. He set up a group chat with his APA students on WhatsApp and told them to contact him anytime — really, anytime — they have questions. He tries to answer within minutes, even if queries come late at night, early in the morning, or over the weekend.

On a recent Tuesday, he led Romero into a breakout Zoom room, began sharing his screen, and pulled up a webpage with the title “Angles introduction.” He read the definition of an angle to Romero, translating from English text to spoken Spanish as he went. He told Romero that it’s important to understand angles.

When Romero leaned away from the screen, one eyebrow drifting upward, Sanchez scrolled down the webpage and began circling his mouse over a picture of a construction worker in an orange vest peering into a theodolite, an instrument surveyors use to measure angles.

He explained what the worker was doing. “See, they use this a lot in real life,” Sanchez said in Spanish.

Romero rocked forward again. Sitting cross-legged on his bed, he put pen to paper and started taking notes.

Source: https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/alexandria-night-high-school/2021/04/11/2be262b2-9226-11eb-a74e-1f4cf89fd948_story.html?wpisrc=nl_sb_smartbrief